Context

Many commonly used terms to raise awareness of antimicrobial resistance, such as ‘the war against superbugs’, risk misleading people to request ‘new’ or ‘stronger’ antibiotics from their doctors or pharmacists rather than addressing a fundamental issue: the misuse and overuse of antibiotics in humans and animals. Simple measures regarding the antibiotic consumption are needed for mass communication.

In this research, we describe the concept of ‘antibiotic footprint’ as a tool to communicate to the public the magnitude of antibiotic use in humans and animals, and how it could support the reduction of misuse and overuse of antibiotics. We highlight that people need to make appropriate changes in behaviour that reduce their direct and indirect consumption of antibiotics. We developed the website to communicate with lay people (https://www.antibioticfootprint.net). We recently developed an antibiotic footprint individual calculator for people to compare their footprint with others, and stimulate the thinking about reducing overuse of antibiotics (https://www.antibioticfootprint.net/calculator/)

Introduction

International health organizations encourage all countries to reduce their use of antibiotics in both humans and animals to a minimum but limited public understanding of antibiotic resistance is a major barrier to the reduction of inappropriate antibiotic use. Antibiotics are often inappropriately used to treat viral infections in humans, including the common cold. A large number of people worldwide incorrectly believe that antibiotics are effective for the common cold and influenza-like illnesses. A recent study in the UK found that information about antibiotic resistance given to participants with low awareness could, paradoxically, lead them to ask a doctor for antibiotics more often (Euro Surveillance, 2018). Therefore, communication messages on antibiotic resistance should be simple, and individuals need to be supported to understand that appropriate behaviour change is important to them personally. In addition, antibiotics are used in large quantities in animal agriculture to maintain animal health while improving hygiene of animals in the farm is considered costly and largely ignored. Consumers are in a strong position to influence the use of antibiotics everywhere. But consumers are poorly informed about existing use globally, which reduces the impetus for change.

Conceptualization of ‘Carbon footprint’ as a model for an ‘antibiotic footprint’

‘Antibiotic footprint’ has been proposed as a global tool for the public communication of the magnitude of antibiotic use in humans, animals, and industry, which could build on the success of the concept of ‘carbon footprint’ (Keen & Patrick, 2013). People need to use energy to live but using too much energy has been driving climate change globally. Likewise, people and animals need antibiotics if they are infected with bacteria. However, overuse and misuse of antibiotics in humans and animals are fostering antibiotic-resistant bacteria and will increase the global number of human and animal deaths they cause over time.

As a carbon footprint measures the quantity of consumption (consumption footprint) converting to the quantity of gaseous emissions (emission footprint) relevant to climate change and is associated with activities such as automobile use, building heating and agriculture (Figure 1), an antibiotic footprint can be used to attribute antibiotic consumption to different human activities. This includes direct consumption of antibiotics at community and hospital levels, and indirect consumption, for example via animals bred for food or unsanitary environmental conditions. Antibiotic footprint also aligns with the concept of one health since antibiotic footprint considers antibiotic consumption in all sectors, including human, animal and environmental health.

Figure 1. A conceptual figure for carbon footprint (left) and antibiotic footprint (right) (Source: Limmathurotsakul, D et al., 2019)

Figure 1. A conceptual figure for carbon footprint (left) and antibiotic footprint (right) (Source: Limmathurotsakul, D et al., 2019)

Simple measures of consumption are needed; carbon emissions are measured in units of grams/kilograms/tons of carbon-dioxide and ‘antibiotic consumption’ could be measured in units of grams/kilograms/tones of antibiotics as a total value, or per head of population. Currently, many indicators are proposed and used for antibiotic consumption in human and animals, including the DDD (defined daily dose) per 1,000 inhabitants per day and milligrams per Population Correction Unit (PCU). DDD is a standard unit for pharmacists, and PCU is a standard unit for veterinarians. These terms were created to support fair comparisons among different antibiotics and different animals included in the calculation but are complex terms. Learning from carbon footprint, it is likely to be better to design the public communication strategy around antibiotic consumption in simple terms of grams/kilograms/tons of antibiotics.

Potential uses of antibiotic footprint

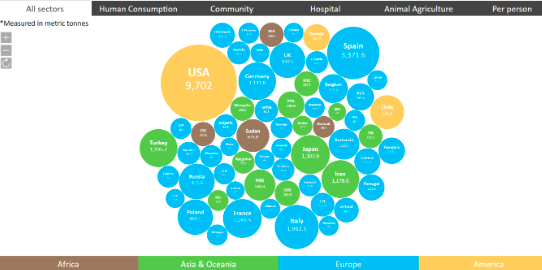

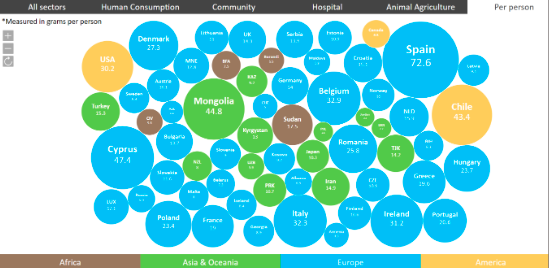

Similar to carbon footprint, the antibiotic footprint of each country with official data could be presented and compared (Figure 2). This information would inform both policy makers and the community. For example, we might define a country’s antibiotic footprint as the total amount of antibiotics consumed in that country. Antibiotic footprint could be estimated by combining the total amount of antibiotics consumed by humans and animals in a given country (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Examples of antibiotic footprint by country (metric tons) in 2015 (Source: Limmathurotsakul, D et al., 2019)

Figure 2. Examples of antibiotic footprint by country (metric tons) in 2015 (Source: Limmathurotsakul, D et al., 2019)

Figure 3. Examples of antibiotic footprint per capita (grams per person) in 2015. (Source : Limmathurotsakul, D et al., 2019)

These figures (https://www.antibioticfooprint.net) can prompt people to ask, “How much antibiotics are being used in countries without official data?”. It is worth noting that official data on antibiotic consumption in many low and middle-income countries (including India and China) are currently not available.

Crude comparison of average consumption per capita could also prompt people to ask whether misuse and overuse of antibiotics occur. For example, worked out as an average per head of population in 2015, a person living in the UK is directly consuming twice as much antibiotic as a person living in the Netherlands (8.3 vs. 3.3 grams, respectively). Are antibiotics being overused in the UK at some level? Can overuse of antibiotics be appropriately reduced? What health policies or cultural behaviours explain the difference between these two countries?

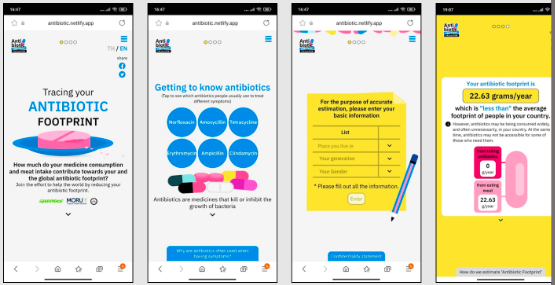

An antibiotic footprint could also be calculated for individuals and support behaviour change (https://www.antibioticfootprint.net/calculator) (Figure 4). As antibiotic use in humans varies by age, gender, local culture, individual attitude toward taking antibiotics, etc., it would be informative to compare ourselves to other people in our own as well as other countries. Similar to on-line calculators for carbon footprint, on-line individual calculators for antibiotic footprint could provide information, knowledge and recommendations about antibiotic consumption that could influence individual behaviour change.

Figure 4. An example of antibiotic footprint individual calculator (Source: https://www.antibioticfootprint.net/calculator)

Conclusion

Other than concluding what the footprint can do and is, in a closing section, could you say a little bit about the usage statistics of the calculator? Has there been any impact evaluations? How effective is it, and how does it compare to traditional health communication instruments? Any ideas on how the footprint has been received? Any plans for the future? Etc. All of these questions are more reflecting on the success or barriers, opportunities or threats of the instrument.

Points of discussion

Pedagogical notes

It is recommended to have the students look at the calculator and do their personal assessment to explore its functions. The trainer can also show the tool in class directly and have students compare and contrast the data of their country of origin with other countries.

Students can discuss their personal experience of communicating about antimicrobial resistance with friends and family members, Would the toolkit have helped then communicate better? Are there other digital tools thinkable that facilitate communication about AMR?

Students can discuss what they perceive as barriers and facilitators of communication and behaviour changes related to solving the problems of overuse of antibiotic use and discuss how policy makers could improve communication and behaviour change related to the problems of overuse of antibiotic.

Acknowledgements

Ravikanya Praphasavat, Sandy Sachaphimukh and Prapass Wannapinij for technical support.

Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok