Introduction

In this case study, I will present a summary of a chapter of my PhD thesis, discussing the UK’s dairy supply chain governance of responsible antibiotic use.

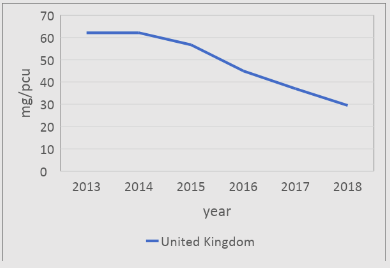

In the United Kingdom (UK), the livestock sectors are expected to drive and standardise responsible antibiotic use across farmers in accordance with national and international guidelines (Department of Health, 2016). According to latest antibiotic sales data published by the UK’s Veterinary Medicine Directorate (VMD) (UK-VARSS, 2019), the UK is reducing their antibiotic sales of food-producing species and is one of the better performers in the EU (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The UK’s veterinary antimicrobial sales in mg/PCU 2010-2017 (UK-VARSS 2019)

In contrast with the pig and poultry industry, the UK dairy sector has only recently started to engage with responsible antibiotic-use activities. One explanation for this difference between livestock sectors is that according to the UK-VARSS reports published over the last decade, the dairy and other food producing sectors use significantly less antibiotics than the pig and poultry industry. The British media have also played an important role in shaping the debate (Morris, Helliwell, and Raman, 2016). The “factory farms” in the pig and poultry industry were framed as the most drugged-up food animal sectors (Fenton, 2016; Levitt, 2016). Less intensive farming sectors escaped public scrutiny, which allowed those sectors to continue with their antibiotic practices. However, the O’Neill reports of 2015 and 2016 and the UK Government policy response to O’Neill (2016) made all livestock sectors and their food supply chains responsible to govern responsible antibiotic use and to produce evidence of these activities. The aim of my study was to analyse how responsible antibiotic use was rolled out in the UK dairy sector (Begemann et al., 2019). For the purpose of this case-study, I confine the analysis to UK dairy supply chain actions.

Methodology

Using a constructionist approach (Green and Thorogood, 2004), I analysed how the UK’s dairy supply chains developed antibiotic policies in accordance with their own concerns, interests, knowledges, and supply chain activities. A multi-sited ethnography was used to tackle the bounded territories of single-sited ethnographies (Marcus, 1995). This methodological approach enabled me to study how dairy antibiotics as “ethnographic objects of interest” were governed across dairy supply chain contexts: e.g. retailers, milk processors, farmers, farm assurance systems, dairy lobby groups, veterinarians (Latour, 2005). Ethnographers often employ a variety of qualitative methods, tailored to the demands of the research site(s) (Barbour, 2001). In this study, methods were used in a flexible manner in accordance with the sites of a multi-sited ethnography. This meant that in some sites I requested documents, interviews, observations, focus groups or a combination of these.

During the initial stage of fieldwork, my first research participant turned out to be a key informant, shaping the next steps I took in my research. This was a veterinary surgeon specialised in dairy herd health with links to a large retailer. Although the interview started off as a semi-structured interview with some key topics, we ended up talking about a variety of issues in the UK dairy industry that concern dairy antibiotic use. I learned about the complexities involved with regulating dairy antibiotic use, and the vet provided me with important actors, such as milk contracts, milk residues, milk prices, retailers, and milk processors. This key informant introduced me to other dairy supply chain stakeholders, such as a retailer, a dairy processor, a pharmaceutical representative and two lobby group representatives in his network. Through “snowball sampling”, these participants introduced me again to other dairy supply chain stakeholders in their network who were willing to participate in my study. The same processed happened after recruiting three veterinarians through the University of Liverpool, via whom I was able to recruit more veterinarians (19), veterinary consultants (2), and veterinary practices across the country for fieldwork observation (for more information on the methodological approach see Begemann et al. 2019).

Responsible antibiotic use in the UK’s dairy supply chains

In the UK, private food supply chain standards – the Dairy Red Tractor Farm Assurance Scheme*, milk processor milk contracts (75% of UK farmer population) and retailers milk contracts (25% of UK farmer population) – play a central role in definitions, expectations, and farmer practices of milk safety and quality. These private-led standards also include responsible antibiotic use standards, to be executed by farmers. Fieldwork data reveal that responsible antibiotic use standards and their practices are tailored to economic concerns in dairy supply chain contexts, rather than addressing concerns about AMR per se.

Milk processors concerns: milk residues

When medicines are used in food animals, they can leave residues in animal derived products that could pose potential harm to consumers. To protect human health against antibiotic residues in animal products, antibiotic withdrawal periods have been established for each antibiotic product (Council of the European Union, 1996). The antibiotic withdrawal period is the statutory period that should elapse between the last day of antibiotic treatment and the point at which the food-producing animal or its products enter into the food supply chain (FSA, 2016). Inside this statutory withdrawal period, food-producing animals or their products cannot be used for human consumption. The main responsibility for antibiotic residue management in dairy lies with the milk processors (and is as such industry-led). Milk processors need to ensure as such that their milk is “safe” from medicine residues to keep the trust of official authorities (FSA) and the retailers they supply (FSA, 2015).

A representative of a dairy lobby group expressed that milk processors are since 2016 under pressure from the UK Food Safety Authority to improve their milk residue management. To milk processors, farmers are considered as the biggest risk to antibiotic milk residues. To improve responsible antibiotic use by farmers and to reduce the risk of antibiotic residues entering in dairy supply chains, milk processors started to implement antibiotic workshops, antibiotic training schemes, video’s, and protocols. Some of the milk processors also incentivise the use of antibiotic self-test kits by their contracted farmers or use milk price penalising systems to make antibiotic use less attractive. Most of the UK’s milk processors mainly rely on the Dairy Red Tractor Scheme to improve animal health and welfare. As such, economic concerns around antibiotic milk residues drive the focus of antibiotic policies instead of milk processors tackling structural problems on their contracted farms in the first place.

Evaluating how farmers implemented milk processor antibiotic policies, farmers identified the differences between artificial workshop settings and farm realities. While artificial “classroom” settings fostered communication and knowledge exchange between farmers it did not reflect the reality of working on a farm. As one farmer argued, “you need to get mud on the boots and get out there” when learning new farming practices. The milk processor SDCT protocols/workshops fail to address these farm complexities as they reduce antibiotic use into a technical performance. Equally, veterinarians argued how knowledge transfer tools such as protocols, training, and videos were not always adopted by farmers as expected by industry policymakers. Some vets argued how farmers simply refuse to change practices and find “all sorts of critique” to the teaching videos. Problematically, the findings of my fieldwork illustrate that the Dairy Red Tractor Scheme is a paper reality, rather than reflecting true practice. Most dairy supply chain actors require farmers to be Dairy Red Tractor farm assured, but farmers do not get financially rewarded in return. Consequently, farmers see the Red Tractor Scheme as a tick box exercise to get them milk contracts, rather than a mechanism they can use to innovate their farms. Finally, farmers might dispose of more milk in the environment rather than let milk residues enter the food chains, although the environmental AMR burden of this practice is yet, unknown. So, although milk processor policies might result in less antibiotic residues in the food chain, irresponsible antibiotic practices on the dairy farm continue with unknown veterinary/public health and environmental effects.

Retailer concerns: consumer profiles

To reduce media and consumer concerns, retailers need produce “evidence” of “responsible antibiotic use” activities in their supply chains. Importantly, there is a difference in consumer profiles between retailers: quality sensitive consumer profiles expect high milk quality standards and are willing to pay more for their milk, price sensitive consumer profiles prefer affordable priced milk. Each retailer has a certain consumer profile to which they adjust their products. With the issue of responsible antibiotic use, fieldwork data reveal how UK retailers align their responsible antibiotic use standards to their consumer profiles, rather than collectively addressing the issue. Due to media pressure (Harvey, 2017), most of the UK retailers were at the time of my fieldwork either designing or already implementing antibiotic surveillance systems. Retailers with quality sensitive consumer profiles were implementing additional antibiotic standards, which was supposed to increase “responsible antibiotic use” and consequently, herd health (less use of antibiotics on farms means “healthier” herds). Similar as to milk processors, retailer economic concerns around dairy antibiotics drive the content of antibiotics standards.

During fieldwork observations and interviews, it became clear how industry stakeholders were aware of farmers “off the record” use of antibiotics. Farmers themselves revealed that farmers, as a group, have access to prescription drugs through their secret stocks, black markets, neighbours, and double milk contracts. Some of the farmers falsify records, as they are either afraid to lose their milk contract with retailers or as they want to belong to the best performers of the group. One farmer reported that he had seen a farmer losing his milk contract when he raised his opinion during a retailer meeting. The fear of losing their milk contract potentially pushes farmers to find ways to get antibiotics without prescription and recording. Problematically, the reliance of retailers on antibiotic surveillance data creates ignorance to practices outside the reality of data. At the same time, although antibiotic training and workshops were popular methods to inform policy, industry, and supply chain actors about policies, farmers saw attendance as an obligation associated with their milk contract. Farmers are evaluated whether they attend retailer meeting and workshops. As such, farmers will take the effort to show up at meetings. But instead of engaging with the knowledge-transfer programmes, some farmers see the retailer farmer meetings as a nuisance that disrupts their day. Although retailers then believe they have successfully transferred their policies through interactive sessions, farmers will continue with their daily routine practices. Finally, industry stakeholders were arguing how retailers use antibiotic standards to differentiate from each other, rather than unifying approaches. Fragmented farmer antibiotic practices with large differences in herd health performances across the country are the result.

Conclusion

The multi-sited approach of this study revealed how antibiotic policies and their practices differ across dairy supply chains sites. Rather than imposing knowledge upon the research field, I led research subjects (documents, sites, people) define their concerns and actions around dairy antibiotics. Fieldwork data shows how different antibiotic concerns of retailers and milk processors, situated in market interest, translates in a different policy focus. Consequently, this segregates the dairy farmer landscape in their antibiotic practices rather than unifying it. The different content and practices of antibiotic policies across the dairy supply chain can potentially impact how AMR develops and travels across systems. Even though there is awareness across the dairy supply chain that farmers very often do different things to what they say they do, antibiotic surveillance data of retailers and the latest annual UK-VARSS report of 2018 shows progress is being made and knowledge exchange programmes have been successful. This leaves structural problems in the agricultural networks of farmers that contribute to antibiotics to be unexplored.

BVSc MVSc MSc – Post doc researcher University of Wageningen and former PhD researcher at the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Emerging and Zoonotic Infections, Institute of infection and Global Health, University of Liverpool.

* To unify transparency across Farm Assurance Schemes, the British food industry introduced in 2000 the “British Farm Standard” known as the Red Tractor symbol. The Red Tractor standards are species- or product-specific and stand for production standards covering the harmonisation of animal welfare, food safety, traceability, and environmental protection across food producers (Red Tractor 2020). The Red Tractor Farm Assurance Scheme is voluntary which means farmers are not financially rewarded if they commit to the standards. In the UK dairy supply chains, farmers are required to be Dairy Red Tractor Farm Assured.