Introduction

The AMIS Uganda Project is part of the AMIS Hub, which is a collaborative research program led by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), with IDRC (Uganda) and Mahidol University and Ministry of Public Health (Thailand) as partners. The AMIS Uganda project is a four-year social science study aimed at better understanding the roles of antimicrobials in society and everyday life. We set out to identify how antimicrobials shape and enable ways of life within households, healthcare facilities, among urban workers, and in animal farming. By addressing how people actually use antimicrobials, and the wide-reaching reasons for reliance on these drugs, we will provide a detailed account that can be used by policy makers working on antimicrobial resistance in Uganda. Using established social science methods, we provide fresh approaches to the study of antimicrobials in Ugandan society, to demonstrate how antibiotics are linked to social, economic, and political systems. Our research focuses on antibiotics, but also includes antimalarials, antiretrovirals and antifungals.

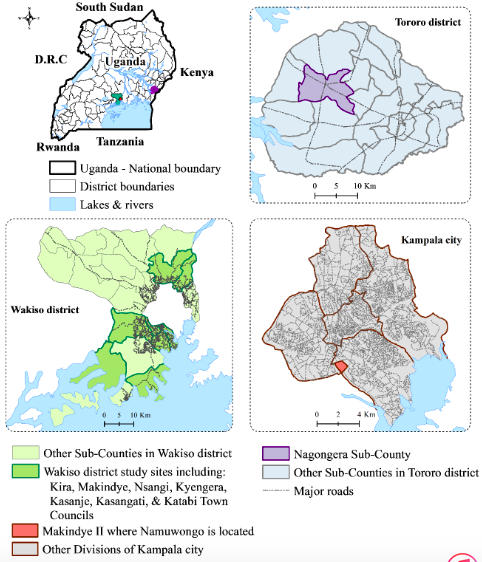

Project sites in Uganda currently include Nagongera (Tororo), Namuwongo (Kampala) and Wakiso (see Figure 1 below). Tororo district in Eastern Uganda is a rural area where most residents engage in agriculture as their main economic activity. Nagongera Sub County in Tororo, just like most areas in eastern Uganda, is a place long neglected by governmental programs and existing within and between piecemeal well-meaning NGO efforts. Namuwongo in Kampala capital city is a large informal settlement where many people who work in the city centre and the surrounding affluent neighbourhoods reside. Wakiso district is a peri-urban area approximately 20 kilometres northwest of Kampala. It is an agricultural district which has been ranked as a top producer of poultry and piggery in Uganda.

Key definitions

Through our research we have developed the following working definition of quick farming: it can be understood as a phenomenon that combines rapid production of meat (through exotic breeds, commercial feeds); smaller space of production (confinement housing); increased financial investments (biological inputs, utilities, and infrastructure) and forms of caring through medicines (antibiotics, antimicrobials, and nutritional supplements).

Precarity has been defined by Judith Butler 2009 as a politically induced condition in which certain populations suffer from failing social and economic networks becoming differentially exposed to injury, violence, and death. Precarity also entails lack of stable work, steady incomes, unpredictable cultural and economic terrain, and conditions. Precarity is experienced by marginalized, poor, and disenfranchised people who are exposed to economic insecurity, injury, violence, and forced migration.

Figure 1: Map of study sites – Nagongera (Tororo), Namuwongo (Kampala) and Wakiso.

Healthcare: Experiences with antibiotics from the rural Tororo district

As I walk up the dusty main road leading up to Harriet’s home in Nagongera Sub County, Uganda, I notice that the gardens in almost every homestead are filled with people uprooting groundnuts from the dry and sandy land. Using the foot path beside the huge rock in front of Harriet’s house, I make my way past the cows grazing on one side of her compound. I sit on a stool in the kitchen to chat with Harriet. As she prepares the one meal of the day that she can manage to provide for her five children, she tells me about the medications she and her husband were prescribed this morning and asks me whether the purple and black capsules (referring to Ampiclox) treat everything. She explains to me that they have been receiving Ampiclox a lot at the research clinic where her whole family is enrolled as study participants.

A rural household in Nagongera,Tororo district where ethnography is being conducted

She expresses to also be concerned about the possible effect of taking Ampiclox alongside the Doxycline that she only managed to obtain today, even though she was told to buy it a few days back as part of her treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease. A month ago, Harriet was told by the clinician at the nearby health facility to get a scan done in a private health facility, but she was then unable to raise the money to cover this cost. When the scan was finally done one month later and confirmed pelvic inflammatory disease, she was prescribed ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and paracetamol and asked to buy Doxycline which was out of stock at the time.

Harriet strikes me as a very organized woman: she has seven children including two who are away from home and over whom she continues to worry. She manages to get food on the table, enrol in the various schemes on offer for planting groundnuts, and make herself available to relations in the city to care for their animals. However, in the context where she lives, Harriet is very much alone in shouldering responsibility. When the groundnuts do not grow because of climate instability, she has to repay the loan. When the animals are stolen, she has to find the funds to replace them and begins to sleep with them inside the house to avoid similar losses. When her persistent pelvic inflammation requires treatment, she is the one who must find money to pay.

Farming: Experiences with antibiotics from the peri urban Wakiso district

“Quick farming: is it a recipe for antibiotic use?”

A morning drive through the heavy city traffic to the eastern side of Wakiso district, leads us to Kira town council. Mzee Byenkya’s poultry farm has been our ethnography study site this season. He is a soft spoken, eloquent man, in his late 50s. Born and raised in the city, poultry farming has led him to live in the fringes. Without any experience in exotic poultry farming, establishing this farm was a key retirement goal. The farm sits on 2 acres of land stretching from a busy dusty road inland. Two-thousand brown laying chickens are raised here, in double story – corrugated iron sheet structures. ‘It is three years now’, he says. Inspired by the hearsay lucrativeness of this venture, raising these two batches of chicken has been a learning curve. Prestige, new friends and having folks interested to learn from this farm are aspects of his new enterprise that he is keen to tell me about.

A poultry farm in Wakiso district where ethnography is being conducted. (Photo by Magdalena Bondos, LSHTM ©)

However, poultry farming has not been straightforward. Mzee Byenkya is always preoccupied with the status of his chickens. With these “exotic” breeds, he knows they are vulnerable to infection as well as to theft. He pays close attention to their behaviour – listening to their chuckling, observing their agility, monitoring their droppings, feeding and egg laying pattern. Changes in any of these signs could mean infection. A man on a mission, he is! On a regular morning, Mzee Byenkya will conduct a thorough inspection of the entire exterior of the farm. With long confident strides, he walks through the many

chickens, picking up some to take a closer look

at their eyes, feet, and bottom. He is keen to recognize the weak and dozing; isolate the underweight; and check for eggs in the laying boxes plus popular laying corners. Today, five sick chickens are singled out because of illness. Just as we try to figure out what disease it may be, the expected number of egg trays is not attained too! Lost in a deep gaze, thoughts race and linger on in the man’s mind. Only for him to dash into his room and come out holding a spoon and Tylosin powder – an antibiotic and a feed additive. Drinking water is the medium. And later with a huge smile on his face, he concludes ‘More eggs tomorrow’.

Urban work: Experiences with antibiotics from the urban Kampala district

“Four red and black capsules”

Mary was recently involved in a motorcycle accident and sustained several wounds on her legs and shoulder—or at least those are the ones I can see. The wounds were going septic, and they gave her a fever the night before I spoke to her. She had no money for a full dose of the antibiotics recommended by a friend but was able to buy just four pills from a local drug shop, which she described as red and black capsules. As we talk, I am distracted by the houseflies buzzing around the wounds on her legs. She occasionally fans off the flies with a piece of cloth that she is using to cover the biggest wound. She recognizes that she will need more medicine to feel better but just does not have the money to afford a full course of antibiotics. She says a friend had earlier recommended Ampiclox when the accident happened, but she did not have money to buy the medicines at that time either.

A major drainage channel in Namuwongo after heavy rain. (Photo by Magdalena Bondos, LSHTM ©)

Mary lives in an informal settlement in downtown Kampala, where she pieces together a variety of insecure jobs every week to get by. The pay is never enough, and her contracts are only ever short and verbal. Her work is always precarious. I have seen her wash people’s clothes and cook for the builders at a building site close to her home. She was recently promised work as a domestic worker at a nearby home in an affluent neighbourhood. This job promises a bit more consistency and slightly better pay, but that has not materialized yet. For the past few days, while recovering from her injuries, she has not been able to work, making the prospect of purchasing the antibiotics she needs unlikely. She worries that while injured she could go days without any job offers.

Conclusion

Spending quality time with people like Harriet, Mzee Byenkya and Mary allows us to understand and document the everyday realities of health, farming, and urban work, and to learn how antibiotics fit in these spaces. The story of Harriet shows us that unlike the narratives from the reports written thousands of miles away that state that ‘people are eating antibiotics like sweets’, that rather these medicines are substances for Harriet and her family that are woven into the care she is responsible for providing to herself and to her family, amidst acute uncertainty and chronic precarity. Mzee Byenkya’s reliance on an antibiotic to fix the illness that threatens to interfere with his poultry production business indicates that the traditional roles of antibiotic medicines are revolutionizing everyday life. With precarious livelihoods in quick farming, antibiotics offer a crucial sense of stability and continuity of farms without which financial investments and livelihoods are at risk. Just like Mary, many other people we studied are in unstable economic standing, engaged in precarious employment and most of the time unable to afford their basic needs, let alone a full course of antibiotics. Her experience demonstrates the complexity of a singular act of taking medicine and shows how antibiotic use can be influenced by many things happening in the background. The vignettes challenge the narrative of “irrational” medicine use, instead bringing to the fore how individuals may find themselves in situations where-antibiotics are tightly entangled in daily functioning and survival even when it involves taking an incomplete dose of antibiotics.

Butler, J. (2009). Performativity, precarity and sexual politics. AIBR: Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana 4(3):I-XIII. DOI: 10.11156/aibr.040303e.