Context

India accounts for 27% of tuberculosis (TB) burden globally, one-fourth of global drug-resistant TB cases, and 32% of TB deaths. (Raviglione, ,2007). The cornerstone of India’s TB control efforts is the Anti-Tuberculosis Treatment, which effectively reduced TB patients’ mortality over decades. The successive TB programs since the 1960s have ensured free TB treatment and diagnostic services to all patients, especially those from socio-economically weaker and vulnerable sections of society. This helped in achieving better case detection and cure rates among TB patients.

Despite these positive efforts made by the TB control programme of India for decades, there are still bottlenecks that persist in terms of treatment success and adherence and emergence of drug resistance among TB patients, especially among certain regions and subpopulation groups. (Tola, 2015) While there has been a multitude of studies on the factors that decide treatment course and adherence, there is less perspective on how the social networks of TB patients play a role in this. Assessing the social networks of a TB patient is essential to understand the enabling patient environment which influences his or her treatment adherence, and related health-seeking behaviour. The enabling patients environment is also important for navigating the treatment cascade successfully and thereby avoiding unfavourable treatment outcomes like treatment failure and drug resistance . The social network framework we adopted views TB patients as a part of their social bonds rather than a disconnected individual nor a mere unit of the health system. Such a framework would help understand how the individuals are impacted by their social network structures and functions in the context of their treatment.

To assess this impact, we have undertaken a social network assessment of TB patients who underwent treatment and their families in an urban district of Tamil Nadu, South India. The disease disproportionately affects the population in the urban slums of the city (Dhanaraj, 2015). Many parts of this city, in general, have a lack of access to safe water, poor quality of housing and overcrowded environments, which contribute to the high burden of TB. An exploratory ego-centric method was used for conducting the social network assessment. (Nagarajan and Das 2019). “Ego” in this study context denotes the TB patients who are the primary participant, and the social network members are referred to as their ‘alters’ or social network contacts of the ego. The alters could be family members, extended family members or relatives, companions, or friends, occupational and neighbourhood contacts, among others. Ego-centric network approach looks at how personal health behaviours, treatment practices are impacted through the personal interactions of TB patients with their social network Information on the social network support received by the participant was probed and we explored how it played a role in the treatment success of patients who live in that resource-constrained setting.

Role of social support networks in overcoming barriers and fulfilling needs

Our assessment highlights the complexity of the barriers and needs experienced by individual TB patients during their treatment and how the social network-driven support rendered to them was crucial in fulfilling this. Especially in this resource-poor setting with high relevance of poverty, alcoholism, poor housing, crowding, poor health care resources, it was surprisingly noted that a variety of psycho-social and economic supports were made possible to the TB patients through their social networks. It was noted that the TB patient’s social network size was varying from being single to having dozens of close familial, social and friendship and occupational relations. We found that patients who had diverse and numerically large networks relations were better able to cope with the barriers and had a more positive treatment course.

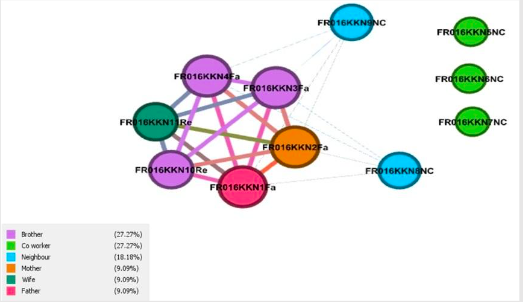

Figure 1 shows the social network structure by type of support for a patient with regular adherence. Forty-five per cent of the network members (coded in violet) provided psychological support for the patient, 18.8% (coded in orange) provided resources as well as psychological and practical support for the patient. Nine per cent of the contacts (coded in blue) provided psychological and practical support for the patient. Twenty-seven per cent of network members (coded in green) provided spiritual, psychological and occupational support for the patients.

Figure 1: Social network structure by type of support for a patient with regular adherence

While these network relations where all characterised by differences in terms of the strength of relations and nature of exchanges between them, overall, they were found to reflect the reciprocal nature between the patient and the relations. Thus, the network relations we elucidated represent the micro-social universe of the patients within which he or she spends most of his relationship time and space and daily exchanges.

In terms of the network mediated support, we found that the patients who were better at navigating the treatment were getting more support from their network members than those unable to cope with their treatment. Patients expressed and experienced a variety of network-driven support, which they highlighted as crucial for their treatment navigation. It ranged from monetary support, non-monetary support, psycho–social support when in need in times of emotional break-up and downsides, spiritual or moral motivation, support for day-to-day work, and work-related support during the treatment period. The positive effect of network mediated support for the patients also implies that they are mitigating the risk of treatment interruptions and the consequential emergence of drug resistance in them. The spectrum of the support needed and expressed by TB patients was very diverse and unique, which indicates that the conventional one-size-fit-all approach to meet the patient’s psycho-social and economic needs may not be useful in addressing them effectively. We identified that spiritual or moral motivations provided by the network members were felt crucial and important by the TB patients, and this factor has not been highlighted in conventional research and assessment pertaining to TB patients’ treatment needs yet. The network support varied across gender, age, socio-economic, and marital status of the patients which underscored the importance of contextual assessments in terms of patient needs. It was also found that the quality of life of patients was in coherence with the social support they received from the social network members. Thus, the outcome of the network dynamics and its support functions extended the realm of treatment outcomes of patients, and it could have a long-ranging impact on their course of post-treatment life as well.

Conclusion

Findings from this assessment highlight the importance of a social network-driven exploratory approach, which could help to understand the network structure and functions of TB patients. Such an approach could help identify the different forms of social network support needed by TB patients in resource-poor TB program settings. The assessment highlights that identifying and prioritising the different forms of social network support needed by TB patients could prove useful to develop social network-based interventions for patient support in the programme and at the community level. The results could pave the way to develop patient centric support systems based on social network-based insights interventions to address the treatment needs and broader social and economic insecurity of TB patients and thereby improving patient outcomes and averting underlying risks of drug resistance. (O’Donnell, 2016).

Points of discussion

Pedagogical notes

PhD Scholar at the School of Public Health, SRMIST, Kanchipuram, India

Centre for Statistics, SRMIST, Kanchipuram, India.